Welcome! The Journey Awaits

How to use this resource?

This does not contain any guides on how to use git. There are tonnes of fantastic resources made by people who know git like the back of their hand. So, this is to signpost you to these resources.

Instead of giving you a laundry list of all of the resources under the sun, I have selected one or two resources which I think is the best for learning or achieving something. However, best is very subjective. Therefore, I will also include the other resources I have found in a list below the featured ones.

I’ve also included some demos and content from the talk in their respective pages. I personally don’t like looking for information within a video, so the content in those pages are the demos and bits which I think are useful as text.

Terminal?? That sounds scary — here’s why the demos use it

Demonstrating the various git commands works in an IDE, but IDEs can change over time and sometimes obscure what’s happening under the hood. Using the terminal lets you see exactly what’s going on and apply those concepts in any IDE later.

Are there any recordings of the talks in the series?

Missed out on the talks? Or perhaps you’re been 100% sold on using Git and need to try bringing someone else onboard?

Check out the youtube playlist for the series. Or watch the first video here!

Help!! I’ve been bitten by the coding bug! What do I do??

Firstly, stay calm. Don’t panic. It happens to even the best of us. Each path to and from this point unfurls in countless, unknowable directions, with the grace of a cat knocking a potted plant off a tall shelf - chaotic yet inexplicably elegant.

| I want to … | Link | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Learn more skills to help with my research | CodeRefinery workshops | Code refinery “teaches all the essential tools which are usually skipped in academic education so everyone can make full use of software, computing, and data with focus on reusability, reproducibility, and openness.” |

| Basics about unix and programming in Python or R | Software Carpentry lessons | “Software Carpentry is a lesson program within The Carpentries teaching basic lab skills for research computing” |

| Read a book that’s both philosophical and introduces computer science concepts | Gödel, Escher, Bach | This is the first computer science book I ever read. It explains computer science concepts in a very approachable manner and has an underlying philosophical question about how cognition emerges |

| Read a book about creating good software | The Pragmatic Programmer | This book “examines the core of modern software development—understanding what is wanted and producing working, maintainable code that delights its users” |

I don’t believe your “good coding practice” conspiracy theory. Are you just making this up?

Yes, I am. 😉 Check out these resources,

- Blog post: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Research Software Engineering: From PhD to RSE

- The section “What I wish I knew in my PhD” is a great read for people just starting their PhD or in the throes of it.

- Chapter on Version Control in The Turing Way

- The Turing Way is a fantastic handbook for learning more about how to make your research can be reproducible, how to plan and manage your project and how to communicate your research

- The Turing Way is massive and can feel daunting to read. However, they have pathways, e.g. Early Career Researchers, which are a curated list of chapter targeted for the pathway’s audience.

I’ve started using git, does this mean my research is now 100% reproducible?

Unfortunately, it isn’t. There are different levels of reproducibility. Plus, if you’re the only one that can make heads or tails out of it, then others won’t be able to reproduce it either.

Using git certainly is a step in the right direction. However, it isn’t a panacea.

- If you’d like to learn more about how to make your research reproducible, I highly recommend this code refinery lesson on how to build reproducible programs and computations.

- If you’re looking for a more in-depth guide, I highly recommend the Turing Way guide for reproducible research.

GRRR a link is broken…

I apologise in advance. But, things move around on the internet. Please open an issue and I’ll do my best to fix it!

Come across a life-changing resource you would like to share?

Please open a pull request!

Starting with Git

Suggested Resources

| I’m looking for a … | Link | Description |

|---|---|---|

Detailed guide to walk me through the set-up of git and GitHub | Software Carpentry Guide to Version Control with Git | The summary and set up page provides information about how to install git and creating a GitHub Account. Episodes 2 and 3 within the guide are about how to set up git and create the repository. The subsequent episodes provide practical advice on how to use git |

Cheat sheet of git commands | GitHub git cheat sheet | Cheat sheet of git commands with explanation about what each of the commands do. A pdf version is also available |

| Simple English explanation of these fixes I copy and paste when I mess up | Oh Shit, Git?! | My go-to guide for when I inevitably mess up. It helped to demystify fixes which I (dangerously) blindly copied from StackOverflow |

| Simple English explanation of what version control is and why it is important for reproducible research | The Turing Way book’s chapter on Version Control | An approximate 5-minute read which is perfect for sharing with others or PIs to bring them on board with using git |

Book that can tell me everything I can know about git | Pro git book | I do NOT recommend this for beginners. But, if you’re the kind of person that needs to really understand something to use it. This is the perfect resource. |

| Guide that is linked to a course at Imperial College London | Imperial Grad School course - Introduction to git and GitHub | |

| Way to find out about upcoming Software Carpentry workshops | Software Carpentry website about upcoming workshops | This shows upcoming workshops around the world |

| Using Git and GitHub for project management | Git and GitHub for efficient project management and collaboration: a mini-tutorial | Blog post on how git can be used for more than just version control |

None of these work for me… Do you have any others?

Overviews

- Overview of

gitcommands - Git for Beginners: The Definitive Practical Guide - Visual Git cheat sheet

Detailed Guides

- Pro Git book

- The Git Basics chapter covers the most common

gitcommands and operations - If you’d like to use branches, I highly recommend the chapter on Git Branching

- The Git Tools chapter explores “a number of very powerful things that Git can do that you may not necessarily use on a day-to-day basis but that you may need at some point”

- The Git Basics chapter covers the most common

- Git documentation

- GitHub training manual

- Less detailed than the book and documentation

- Very useful information on getting started with

git - Written for teaching developers how to use

gitmaking it very useful for getting to grips withgitand is very practical

More Imperial Grad School Courses

These have been created by the Imperial College Research Computing Service

- Introduction to Git and GitHub for Software Development

- Further Git and GitHub for Effective Collaboration

Another useful course that’s not related to git is Essential Software Engineering for Researchers

Creating a Repository Demo

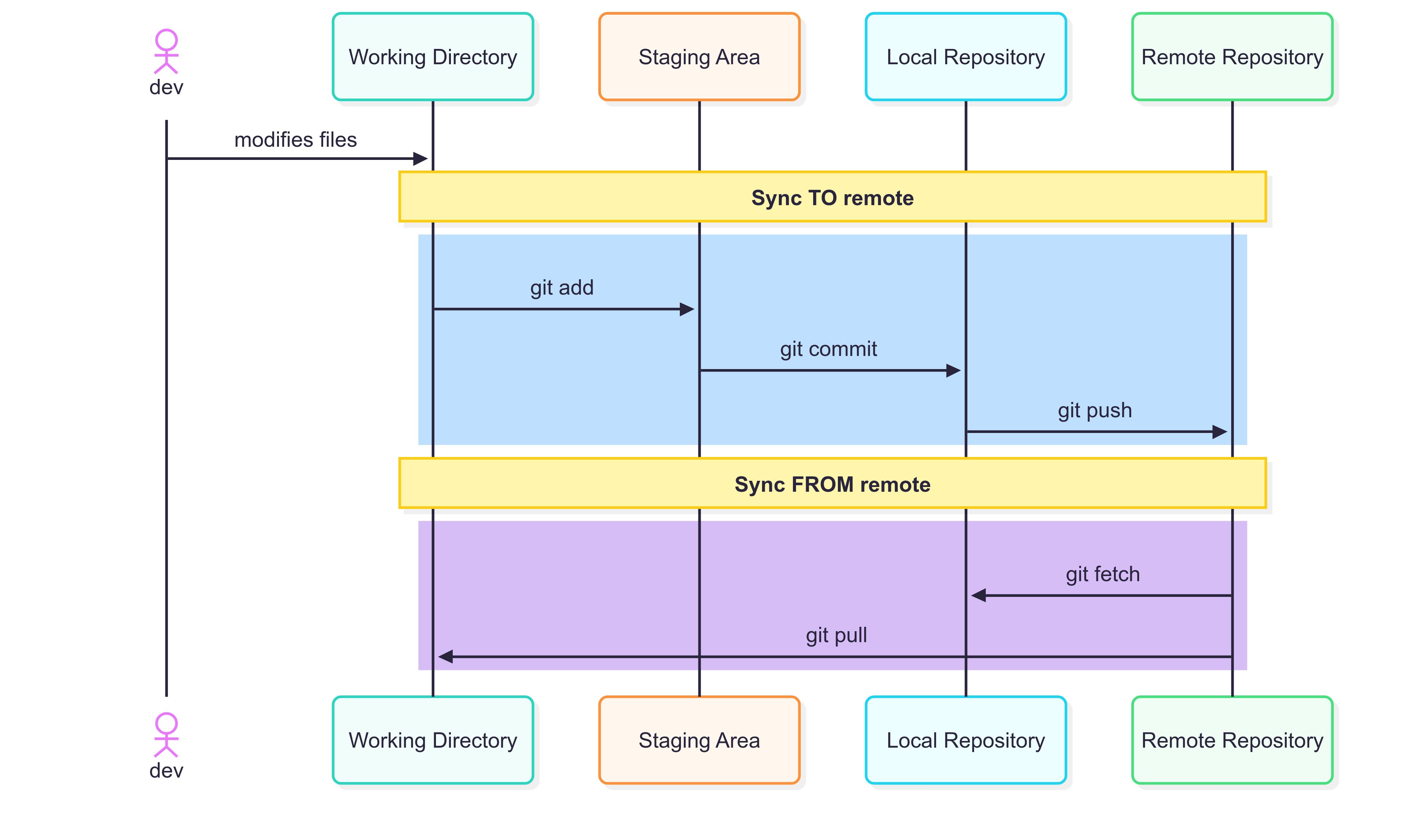

Git’s 3 Magic Words - add, commit, push

“Scroll of Arcane Git Commands”

To Add or Not to Add?

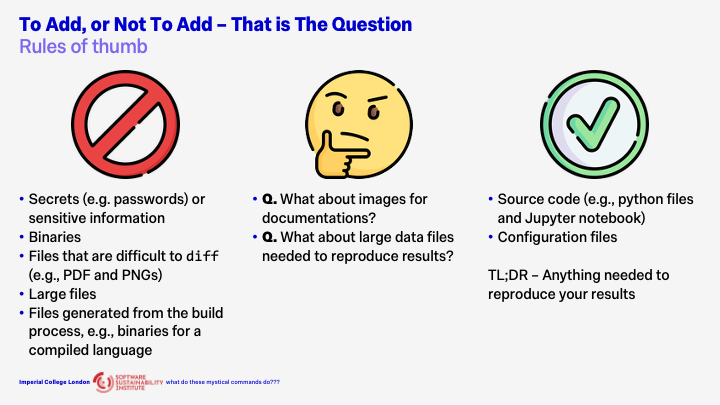

When working with Git, a key consideration is determining which files should be tracked in version control. While there are general best practices, each project’s requirements may differ, and some flexibility is often needed. The following guidelines outline what should and should not be included in a Git repository.

What Not to Add?

Secrets and Sensitive Information

With one crucial exception, never commit secrets or sensitive data to Git. This includes passwords, API keys, private credentials, and any confidential information. Even if a file containing such data is deleted later, it remains in the repository’s history. Fully removing it requires rewriting that history—a complex and error-prone process that poses significant security risks. This rule is absolute and must not be broken.

Binary Files

Binary files should generally not be added to Git. Git is designed for versioning text-based files, allowing it to efficiently track line-by-line changes. Binary files, such as executables or compiled libraries, cannot be diffed effectively. Including them will degrade performance, increase repository size, and may exceed hosting service limits such as those enforced by GitHub.

PDFs, Images, and Other Non-Text Assets

Files like PDFs and PNGs also present challenges because Git cannot meaningfully compare their contents. They can bloat the repository and slow down operations. However, exceptions exist. If your project is small, the files are impractical to reproduce, tied closely to the source code, and change infrequently, including them may be appropriate.

Large Files

Even large text-based files can cause performance issues. Such files should typically be managed outside the repository using tools like Git Large File Storage (Git LFS) or other data management solutions.

Generated and Build Artifacts

Files that are generated during the build process—for example, compiled binaries, minified scripts, or templated source files—should not be tracked. These can always be regenerated by running the build again. Excluding them keeps the repository lightweight and avoids unnecessary versioning of transient data.

What to Always Add

The most important items to include in Git are those required to reproduce your results.

Source Code

All project source files should be version controlled. For a Python project, this includes .py files, Jupyter notebooks, and any supporting files such as pyproject.toml or requirements.txt.

Configuration Files

Configuration files for builds, simulations, or development tools are often overlooked but essential. Tracking these ensures that other contributors—or your future self—can reproduce results consistently and reliably.

In summary, commit everything that is essential for recreating your work, and exclude anything that can be regenerated, derived, or stored more efficiently elsewhere.

When Rules Conflict

Certain cases naturally blur the lines.

For example, while binary files are generally discouraged, images used in documentation are often acceptable. Images can convey information that is difficult to express in text and typically do not change frequently. This repository is an example of when adding PNGs and gifs is more acceptable. (It still isn’t great though…)

Similarly, while large files should not normally be stored in Git, there may be situations where they are necessary for reproducibility. In these cases, it is best to use dedicated tools or external storage solutions while keeping references within the repository.

Useful Tools

.gitignore

A gitignore file specifies intentionally untracked files that Git should ignore. This can help to prevent accidentally adding files that should not be in git from being added to the git repository.

If you’re looking for language-specific templates, this repository has templates which you can download and use for your project.

Pre-commit

Pre-commit is a framework for managing and maintaining multi-language pre-commit hooks. Git hook scripts are useful for identifying simple issues before submission to code review.

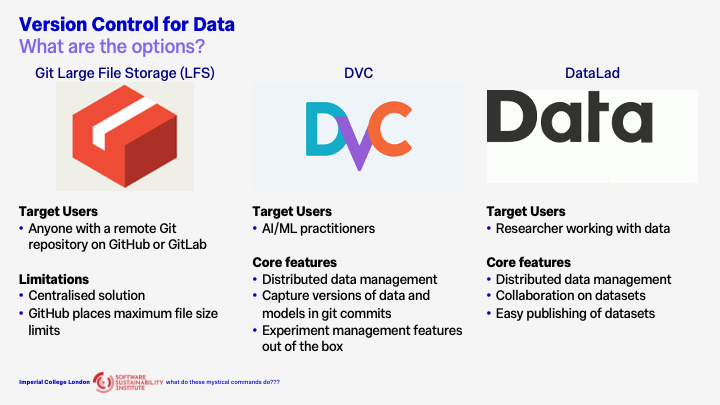

Version Control for Data

For more details, check out The Turing Way’s Guide on Version Control for Data

Demos

If you’re looking for a more visual demonstration of how these git (and more) commands work, check out this fantastic visual simulator of your Git commands!.

What happens when a tracked file is edited?

What happens when an untracked file is edited?

Does restoring staged changes lose all the changes?

Thankfully, it doesn’t! It just removes the changes from the staging area.

This demo show what happens when the file is untracked,

And this is what happens when the file is tracked,

How do I make a commit?

The demo shows how to make a commit while being confident that only the changes you want are committed.

Commit Messages - A Time Machine into the Past

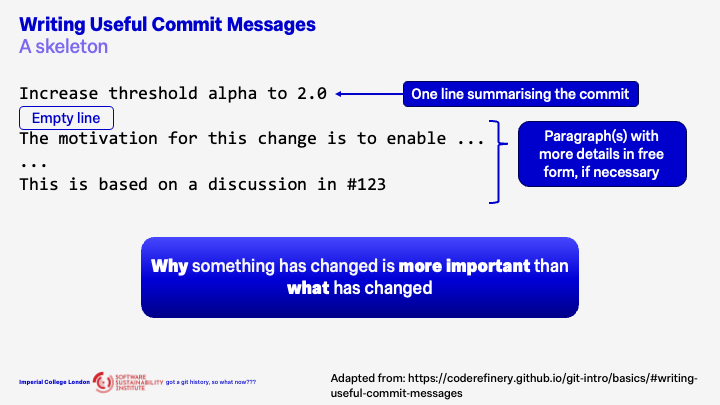

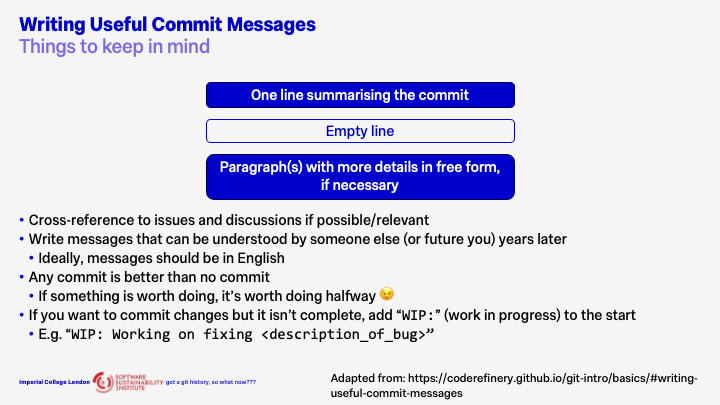

Skeleton for Effective Commit Messages

I highly recommend checking out this website which is where the content in the slides below were adapted from.

Tips for Writing Effective Messages

Atomic Commits

Demos

Note: The explanation in with the demos have been converted from my script to a prose format with the help of the little helper called ChatGPT. I have read the output when formatting it properly for markdown, but might’ve missed something. Please do submit an issue if you spot a mistake!

Why are non-atomic commits problematic?

When a commit contains multiple unrelated changes, it becomes difficult to understand the purpose of each individual difference. Reviewers (and even your future self) have to spend extra time untangling which change was meant to fix a bug, which was a refactor, and which was just a formatting tweak. This slows down code review, increases the chance of mistakes slipping through, and makes it harder to revert or isolate a single change later.

This demo illustrates how combining multiple, unrelated changes into a single commit can make it difficult to understand, review, or separate those changes later.

During the demo, we scroll through a commit that includes two distinct modifications: 1) a logic bug fix; 2) an update to how the closest pressure level is computed

From the commit message, it’s clear that both of these updates are grouped together in one commit. As we inspect the diff, the following observations can be made:

- The first few lines of the diff correspond to changes related to the closest pressure level calculation.

- The next set of lines mixes both the logic fix and the pressure level computation changes.

- The remaining changes are again focused solely on the closest pressure level logic.

This structure makes it difficult to isolate one change from the other. If we later decide that these changes should be split into separate commits — for instance, to improve clarity or to revert only one part — it becomes cumbersome and error-prone.

The key takeaway is that small, focused commits are much easier to manage. When each commit represents a single, logical change, it’s simple to combine them later if needed, but splitting them apart after the fact is much harder.

Why atomic commits are important for revert errant changes?

This demo demonstrates how to revert a commit in Git and highlights why it’s best practice to keep each commit focused on a single, isolated change.

From the git log, we can see that the commit to be reverted is the most recent one.

By running git diff between the latest commit and the current state of the repository, we can view the specific changes that were introduced.

Next, using the commit hash from the log, we execute the git revert command to undo the commit. When prompted for a commit message, the default message generated by Git is sufficient, so we proceed without modification.

After the revert operation completes:

- Running

git logagain shows that a new commit has been created to revert the previous commit. - Running

git diffbetween the latest commit and the current state displays the inverse of the original changes — lines removed are shown in red and prefixed with a minus sign (-). - Finally, running

git diffbetween the second-to-last commit and the revert commit shows no differences, confirming that the repository has been returned to its original state before the reverted change.

This demo underscores the importance of keeping commits small and focused. When each commit represents only one logical change, reverting becomes straightforward and predictable. However, if multiple unrelated changes are bundled together in one commit, reverting can unintentionally remove desired updates along with the problematic ones.

How do I use git add -p to select specific changes?

This demo demonstrates how to use git add -p (also known as patch mode) to split larger sets of changes into smaller, focused commits. A key practice for maintaining atomic commits.

When developing, it’s easy to work on multiple aspects of a project at once. As a result, the changes in your working directory may span several unrelated updates. To keep commits meaningful and organized, it’s important to separate these changes into logical parts before committing.

In this demo, we begin with a diff showing many unrelated changes. The goal is to commit only those changes related to documentation.

- Identifying the relevant changes: The

git diffoutput shows a mix of modifications. To isolate the documentation updates, we’ll usegit add -p. - Use patch mode to review and select changes: Running

git add -pbreaks the changes into smaller hunks (blocks of edits). For each hunk, Git asks whether you want to stage it. Typingystages the change, whilenskips it. If a hunk contains both relevant and irrelevant changes, you can instruct Git to split it further, allowing fine-grained control. - Selectively stage changes: We proceed through the hunks, adding only those related to documentation by answering

yornaccordingly. This same functionality is available in most IDEs. - Verify staged changes: Running

git diff --stagedconfirms that only the selected documentation changes are staged. - Commit with a clear message: We then make a semantic commit describing the documentation-related update. Since it’s a straightforward change, additional explanation isn’t necessary.

- Check remaining changes: Running

git statusshows that other modifications are still uncommitted, whilegit logconfirms that the new commit has been created successfully.

This workflow highlights the value of git add -p in maintaining clean, atomic commits. By reviewing and selectively staging changes, you can ensure each commit represents one logical, self-contained piece of work — improving traceability, collaboration, and future debugging.

This looks confusing? What is the point of it again?

git add -p is a slightly more advanced command, and the goal of introducing it here isn’t necessarily to have you use it immediately, but to show that this kind of functionality exists. Once you know it’s possible, you may notice that your IDE offers a similar feature with a more user-friendly interface. The command-line version is simply what’s happening under the hood, and understanding it gives you a clearer picture of what your IDE is actually doing.

Personally, I prefer working in the command line with Git because I’m terrible at remembering the exact sequence of clicks needed to achieve a specific result in an IDE.

The main use case for git add -p is when you’ve been working on a fairly large feature, or on multiple things at once, and you realise that your changes should be split into smaller, more focused commits rather than bundled into one large commit. I didn’t fully appreciate how useful this command was until I had written a fair amount of code.

I also tend to be extremely cautious about what I add to Git and want to have a greater level of control over what gets added. Using git add -p in my day-to-day workflow lets me explicitly see which changes are being staged, rather than relying on what I think has changed in a file. That extra level of visibility helps prevent mistakes and encourages cleaner, more intentional commits.

Branches - A Glimpse into the Multiverse

Demos

How to create a new branch

Switching between branches with conflicting changes

How does git worktree work?